3 - Recognition

When you look at someone, you're recognising they're there.

Recognition is important because it helps with human bonding.

Why is bonding important in this context? Well, it's because in small groups we're dealing with people who are closest to you, and these are the people who you need to bond with the most.

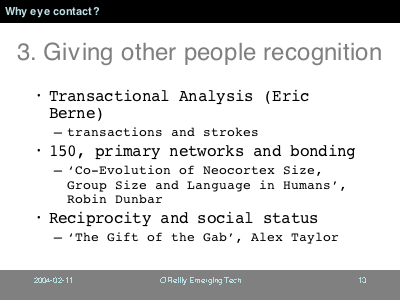

Here's a tool to help think about this kind of thing. Transactional Analysis is a psychological tool from the 1950s. It models communication between people in terms of *transactions*, a request and response. The smallest unit of a transaction, the basic unit of human recognition, TA calls a *stroke*.

It's a nice way of thinking about it: recognising someone, making eye contact with someone, is a stroke: think of protohumans on the African savannah grooming one another, swapping strokes.

Now, Robin Dunbar, an anthropologist, talked about grooming in his paper on neocortex size and social group size in primates. He said we have a maximum cohesive social group of about 150. That's the maximum stable size of your community in a given context -- so, we find that scientific research specialities have a size of about 150 people. My mum has about 150 people on her christmas card list. It was the size of early villages across the world 8000 years ago, and in comparable cultures now. It's been the size of army units through the ages. It's the maximum number of buddies the AOL instant messenger server allows you to have.

Actually, 150 is the number of people the social computing centres of your brain can work with. You know, if you're keeping track of who you owe favours, who nicked your berries last time you climbed a tree, that kind of thing. 150.

But actually that number is dictated by how much time you spend grooming your primary network. Primary network? This large social group is made out of many smaller networks.

Dunbar found that the primary network, the small group, they're cohorts. They protect each other, stand up for each, against the big group as a whole. Individuals in too large a social group get stressed; it's important to have your supportive primary network around, and you maintain that by expending effort on them.

Grooming, for chimps, is picking fleas and lice, but we have a way which is more efficient: conversation. Whereas you can only pick fleas from one other person at a time, you can talk to several at once. One of the key characteristics of this kind of grooming, however, is that it's *public*.

This can be seen in the exchange of text messages in Alex Taylor's paper looking at 16-19 year olds in an English school. They send each other quite mundane messages, with their mobile phones, but what's important is the reciprocity. They establish their peer networks and social status, inside their community, by who sent what to whom, and who replied. Taylor said it resembled descriptions of gift-giving cultures in Polynesia.

It's important you can see who's grooming who because it's like a public assertation of "don't mess with my friends". It's meaningful when you publicly put your neck on the line for someone.

The kids simulate visibility of the grooming, the strokes of recognition, by showing each other the text messages. They treat them as things of value to show off.

So SMS is brilliant. The two most important things for what it means to be human: figure out the pecking order in your community and getting dates.

Anyway.